Market

Memos from Howard Marks: Is it a Bubble?Converting obsolete office buildings to apartments can create attractive risk-adjusted returns for lenders positioned to underwrite complexity.

Key Takeaways:

- Demand for housing in certain U.S. cities is making it more attractive to convert older offices into apartments.

- Only about 7,000 building s in major cities qualify, and feasibility depends on disciplined evaluation, targeted policy support and experienced execution.

- Lenders can benefit from reset valuations and faster timelines, earning completion-risk premiums without relying on rent growth.

Across many U.S. cities, older office buildings—designed for a different era of work—now sit disproportionately empty. The bottom 30% of buildings by quality account for nearly 90% of all U.S. office vacancies.1 This has pushed average vacancy rates nationwide to roughly double pre-pandemic levels.2

At the same time, the housing market faces the opposite problem: too many people and too few homes. Home ownership costs have surged in the U.S., outpacing income growth. Buying a new home today requires twice the income it did in 2019.3 That’s driven demand for rentals, but a lack of construction has left the U.S. with a shortage of approximately 3 million homes.4 Both population and household formation are expected to rise steadily through 2029, placing additional strain on already limited supply.

That’s creating a widening gap between the buildings America has and the buildings it needs (see Figure 1). While the conversion of offices to apartments predates Covid-19, the post-2020 reset in office utilization has accelerated activity, particularly in New York City and other major metro areas where housing shortages and construction costs are most acute and government support has helped boost the projects.

As office conversions gain traction, an attractive credit opportunity is emerging in providing capital to finance projects targeting precisely the older assets that lack a viable future as workplaces.

Figure 1: Demand for Multifamily Housing Surges as Obsolete Office Use Declines

Source: Costar.

Many Buildings, Few Contenders

The U.S. has the world’s highest ratio of office space per capita,5 and the average office building is now more than 50 years old.6 But even though the pool of aging, lower-quality assets is large, the universe of viable conversion candidates is limited. Roughly half of lower-grade offices sit in markets without enough population growth to support apartment development, have zoning restrictions that would prohibit conversion to residential use, or have floor plates that are too inefficient to support residential business plans.7

Of the buildings that meet these basic parameters, most are ruled out by economics: Residential rents are too low in many markets to support the cost of conversion without meaningful public incentives. That leaves less than 1% of the roughly 800,000 office buildings nationwide—about 7,000 properties—as plausible candidates,8 underscoring how narrow the opportunity really is (see Figure 2).

While this has kept the market largely in the hands of experienced specialists, that circle is likely to expand as feasibility improves.

Figure 2: The Actionable Universe of Office-to-Residential Conversions

Source: Brookfield Internal Research

Cities are Clearing the Path

Municipal initiatives are beginning to unlock new potential for conversions. In New York, for example, the “City of Yes for Housing Opportunity” initiative is paving the way for approximately 80,000 new homes, alongside expanded conversion eligibility in Midtown Manhattan and a new tax abatement program. These initiatives have helped enhance project feasibility through long-term incentives for developers.

New York’s approach pulls multiple levers at once—broad zoning reform, expanded eligibility and multi-decade tax relief—creating the most comprehensive conversion framework among major U.S. markets. Other cities, including Washington, D.C., Boston and Los Angeles, are pursuing similar models, although their current incentives are narrower, shorter in duration or focused on only one or two of these components (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Conversion Policies Vary Across Major U.S. Cities

Source: Brookfield internal research; Local government websites.

As cities respond to office vacancies and housing shortages with stronger support programs, we expect the universe of viable conversions to expand. Incentives can help offset construction costs and extend feasibility beyond the most efficient, high-rent markets, though execution will continue to favor experienced sponsors and lenders with technical and structuring expertise.

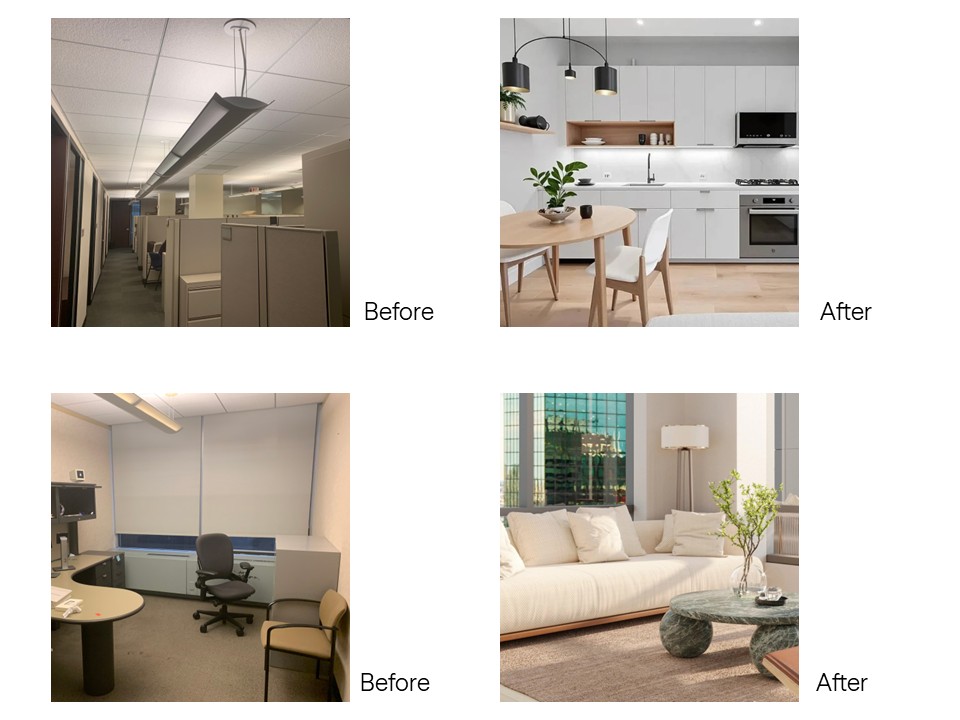

Spotlight: 160 Water Street

Brookfield real estate credit financed the conversion of 160 Water Street, a 22-story office building in Manhattan’s Financial District into Pearl House, a 588-unit residential building. Across three phases of the project, Brookfield provided a total of $650 million in financings.

Photo credits: Top right photo, Vanbarton, Gensler. Bottom right photo, Vanbarton, Williams NY.

The Credit Angle

With equity values in the office segment still roughly 40% below 2022 post-pandemic peak levels,9 new lenders can enter at meaningfully reset valuations. And because only a narrow subset of aging buildings can be viably converted, the opportunity remains selective—rewarding lenders with the expertise to underwrite complexity and act with speed.

Conversions offer clear benefits to credit investors. Because few lenders have the in-house capability to rigorously underwrite conversion risk, return premiums remain elevated even for well-located, high-feasibility buildings. In addition, credit investors do not rely on the same forward rent assumptions that drive equity returns. While conversion economics are improving, equity outcomes can be vulnerable to rising construction costs, lease-up delays and slowing market rent growth. Credit investors, by contrast, are compensated primarily for completion and stabilization risk.

Another benefit is speed. Conversion timelines are typically accelerated relative to ground-up projects of comparable scale—often by 12 to 24 months—so lenders enjoy a faster path to stabilization and repayment, further enhancing downside protection.10 Combine this with strong renter demand in supply-constrained submarkets, and conversion lending offers an attractive risk-adjusted profile.

Selectivity Is Key

Not all conversions are created equal, so lenders need to be selective. Key underwriting considerations include:

Size

Conversion projects require office buildings that are large enough to provide a solid structure and economies of scale for construction cost efficiency, but small enough to lease up quickly.

Location

Successful conversions are typically in neighborhoods with established residential amenities such as shopping, dining and public transit. In dense markets like New York, viability can differ dramatically even between two streets in the same submarket.

Efficiency

Developers that can convert the greatest share of their office square footage into marketable residential units are best positioned to lease up quickly and achieve stronger rent growth. Efficient layouts minimize wasted space, such as irregular corners, unusable nooks and spaces without access to light, and maximize the number of livable units. Depending on efficiency, two buildings with similar square footage can yield dramatically different unit mixes and floor plans, with meaningful implications for project economics.

Sponsor selection

Conversion projects are complex and require institutional-level expertise. Experienced developers can execute efficiently and navigate the regulatory and construction risks that can impede success . While the space continues to grow, only a handful of developers have the experience and track record needed to minimize project risks. Furthermore, a meaningful equity contribution aligns the incentives of lenders and borrowers and provides cushion to the debt position.

Execution Matters

Developers pursuing conversion projects are highly selective in their choice of financing partners. Lenders who stand out share several advantages:

- Integrated underwriting capabilities across both office and residential asset classes

- Speed of execution, enabling projects to move from approval to closing efficiently

- Scale and capital availability, allowing lenders to finance entire projects rather than partial positions

For well-capitalized credit platforms with development expertise, we see an opportunity to deploy capital while increasing the supply of much-needed urban housing.

Sources:

1 JLL, 2024.

2 Moody’s, June 2025.

3 CBRE, 2025.

4 JPMorgan, “A shortage of supply: The housing market explained,” October, 17 2025.

5 Brookfield internal research, as of December 2025.

6 CBRE Investment Management, “Global office report – A two speed market?” 2022.

7 Brookfield internal research.

8 Brookfield internal research.

9 Green Street Commercial Property Pricing Index (CPPI), 2025.

10 Brookfield internal research.

Disclosures

This commentary and the information contained herein are for educational and informational purposes only and do not constitute, and should not be construed as, an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or an advertisement for, any securities, related financial instruments or investment advisory services. This commentary discusses broad market, industry or sector trends, or other general economic or market conditions. It is not intended to provide an overview of the terms applicable to any products sponsored by Brookfield Asset Management Ltd. and its affiliates (together, “Brookfield”).

This commentary contains information and views as of the date indicated and such information and views are subject to change without notice. Certain of the information provided herein has been prepared based on Brookfield’s internal research and certain information is based on various assumptions made by Brookfield, any of which may prove to be incorrect. Brookfield may have not verified (and disclaims any obligation to verify) the accuracy or completeness of any information included herein including information that has been provided by third parties and you cannot rely on Brookfield as having verified such information. The information provided herein reflects Brookfield’s perspectives and beliefs.

Investors should consult with their advisors prior to making an investment in any fund or program, including a Brookfield-sponsored fund or program.